How the Crisis is Opening Opportunities for the Profession

COVID-19 and the Economists’ Redemption

Read a summary using the INOMICS AI tool

The following article first appeared in the INOMICS Handbook 2021.

On a visit to the London School of Economics in November 2008, the Queen asked her hosts why no one had seen the financial crisis coming. It took the professors nine months to come up with an excuse, put forth in a letter in July 2009:

In summary, your majesty, the failure to foresee the timing, extent and severity of the crisis and to head it off, while it had many causes, was principally a failure of the collective imagination of many bright people, both in this country and internationally, to understand the risks to the system as a whole.

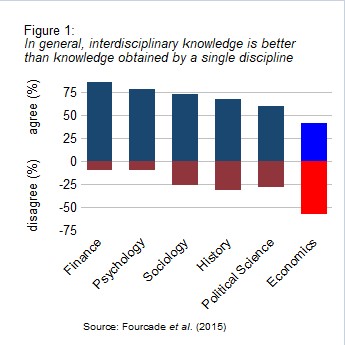

Throughout the subsequent decade, economists sought to repair the reputational damage to their profession. These experts in self-interest had recognized a need to restore public confidence in their work. Economists took it upon themselves to engage in public debate and entire economics curricula were redesigned. Many set out to broaden their horizons through interdisciplinary work with other scientists, something that had hitherto been less common in economics than other social sciences (see figure 1).

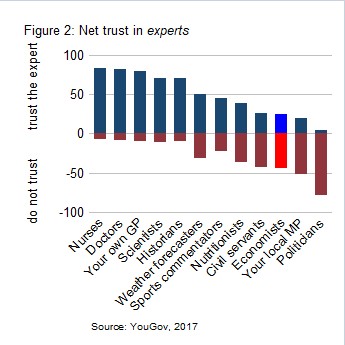

However, despite these endeavors, general attitudes toward economists were little changed. In the United Kingdom, a majority of voters chose to leave the European Union, disregarding the broad consensus among economists that it was going to do them material harm. According to a YouGov poll taken in 2017, economists were among the least trusted of a selection of “experts”, with only politicians faring worse (see figure 2).

In fact, a shortage of trust in economists is nothing particularly new. As far back as 1925, Frank Fetter wrote in the American Economic Review about the relationship between economists and the public, stating,

Academic economists incur popular distrust because they are supposed to echo and reflect the opinions of the business world, while business distrusts them as dangerous radicals because they refuse to worship at the altar of Mammon.

As with their lack of foresight prior to the financial crisis of 2008/09, few, if any, economists saw the coming of COVID-19. The economic impact of the pandemic is huge.

Yet since its primary cause is biological, there has been less finger-pointing at economists this time round. On the contrary, the wide-ranging consequences of COVID-19

have presented a wealth of new opportunities for economists to demonstrate their value to the world. There has been a surge in demand for key skills in statistical analysis and forecasting as governments everywhere face stark choices, weighing the costs against the benefits of various policy alternatives. Economists have found their moment.

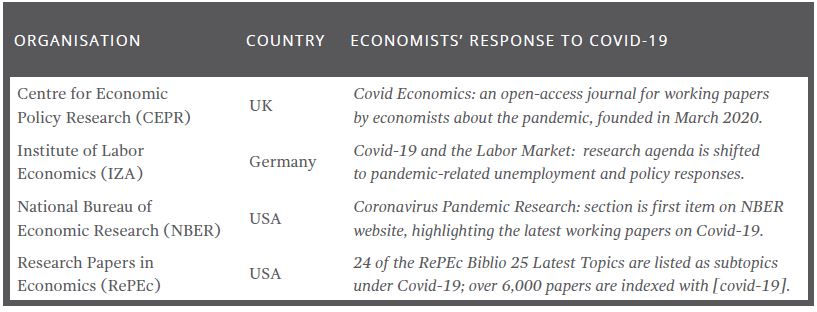

The following table lists initiatives that have been taken in response to the pandemic by some of the major academic bodies and research repositories in economics. Along with papers about the general effects of the pandemic on economies, others focus more directly on the social and health effects of various lockdown policies. A key feature

in many of these studies is the traditional and simple economic approach to problem-solving: the analysis of trade-offs and optimization within a world of ‘second-best’.

The recent hive of activity among economists is not confined to academia. Indeed, there has been a more general realization across society that an understanding of statistics is critical to managing the crisis. The radical changes to daily life imposed by governments around the world have increased uncertainty and the demand to deal with it. Economists have been called upon to reassess markets under lockdown, advise governments on new monetary and fiscal measures to mitigate the economic fallout from COVID-19, and assist more directly in modelling and forecasting the epidemiology of the disease itself.

One of my own areas of research, the voluntary sector and donor behavior, led to my being commissioned to perform analysis of the fundraising market on behalf of charities in the UK. My co-author Cathy Pharoah and I considered the impact of the pandemic both on the various income streams to charities as well as on the new demands for their services. We measured the interdependence between donor trends and economic growth over recent decades to project the future path of charitable donations based on current government forecasts of GDP, acknowledging very large differences between best and worst-case scenarios. In our research report we outline some key pointers for fundraisers to consider, to encourage them to think more as economists when planning their appeals and to focus on what is within their control while being prepared to adapt to new events as they occur.

The US Bureau of Labor Statistics was already expecting higher job growth for economists than for other occupations over the coming decade (14% versus 4% growth, see here. Increased use of “big data” to aid pricing and advertising, in tandem with a more complex and competitive global economy, are cited as the main reasons for the predicted job growth. The coronavirus pandemic is only accelerating such developments.

Economists are trained to analyze data and are equipped with tools that aid decision-making under uncertainty, be that at the individual, group or societal level. While economists may not have been classified among the ‘essential workers’ as the health crisis took hold, they are better positioned than most to show ways out of it and to think beyond. Economists also belong to the group of professionals who can do their job remotely. It may only be thanks to lockdown and social-distancing that the epidemiologists and public health scientists at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine have thus far escaped royal scrutiny on the lack of preventative measures for COVID-19. Having already suffered that fate when the previous crisis hit, economists now have a great chance to redeem themselves. Many of them are already capitalizing on it.

The above article first appeared in the INOMICS Handbook 2021.

References

Fetter FA (1925) “The Economists and the Public”, The American Economic Review 15(1), 13-26.

Fourcade M, E Ollion and Y Algan (2015) “The Superiority of Economists”, The Journal of Economic Perspectives 29(1), 89-113.